Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Every two years, we select a site that we feel is of historical significance in Hague. We then research the site’s history and create a brief text for the marker. On this part of our website, you can find more detailed information about each of the historical sites where we have placed markers.

We are grateful to the Town of Hague for providing financial support for these markers.

Sabbath Day Point's prime location on Lake George was the setting for several battles during the French and Indian War as the French and British fought for military control of this strategically valuable waterway.

In 1757, the French controlled the northern part of the lake from Fort Carillion (known today as Fort Ticonderoga) under Gen. Marquis de Montcalm, while Fort William Henry at the southern end was occupied by British forces under Lt. Col. George Monro. In March 1757, the French laid siege to Fort William Henry. While unsuccessful in capturing the fort, they succeeded in destroying much of the British lake fleet, including more than 300 batteaux, thereby weakening British military control. In June, when Provincial and militia units arrived at Fort William Henry for reinforcement, Monro dispatched 350 Provincial forces from New Jersey to paddle up-lake to assess the remainder of their fleet. Sabbath Day Point, halfway up the lake, was chosen as the best spot for these troops to make camp.

In July of that year, three boats left the southern fort to scout ahead of the campaign but were captured and forced to reveal the British plan. French General Montcalm quickly dispatched 450 French troops and Native Americans to ambush the oncoming British forces. On July 23, the British troops were devastated, with only 100 escaping capture or death; the French had virtually no casualties. Bolstered by his success, Montcalm deployed his troops to Fort William Henry. In the ensuing battle -- immortalized in James Fenimore Cooper’s “The Last of the Mohicans” -- the French were successful and took control of Lake George.

Not ready to accept the status quo, the British returned in 1758 with 15,000 men, commanded by Gen. James Abercrombie, and they again camped at Sabbath Day Point. Though greatly outnumbering the French, the British suffered a stunning defeat, forcing them to retreat. But in 1759, Sabbath Day once again hosted 12,000 British troops under Gen. Jeffrey Amherst, who successfully ousted the French, subsequently changed the fort's name from Carillon to Fort Ticonderoga, and thereafter commandeered the waterways of Lake George.

Sabbath Day Point also served as an encampment during the Revolutionary War two decades later. In December 1775, Colonel Henry Knox stopped there with his battalion on their journey to transport 60 tons of artillery from Fort Ticonderoga to George Washington’s embattled troops in Boston.

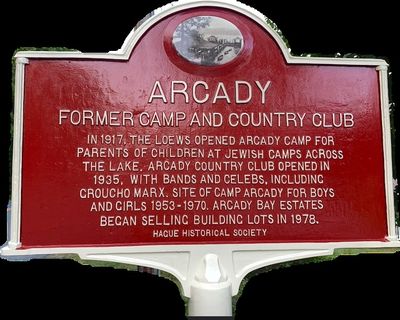

The Arcady story started when Joseph (Loew) Lowe and his brother opened two camps on the east side of Lake George in 1911, Camp Sagamore for boys and Camp Ronah for girls. In 1917, he opened a camp in Hague for the parents of those campers. The adults slept in single-gender tents. Amenities included a nine-hole golf course, four clay tennis courts, plus boating and swimming. Nights were filled with dancing and music.

More importantly, it was a Jewish camp. The first Jewish camp in the Adirondacks, Schroon Lake Camp, was opened by Rabbi Issac Moses in 1906. By 1930, there were 20 Jewish camps on or near Schroon Lake. This is at a time when other establishments actively discriminated against Jewish clientele.

In 1935, Arcady Camp was renovated to become the Arcady Country Club. It was a huge success with a national reputation. Chefs were brought in from New York City to make kosher meals. The Marx Brothers performed. And, of course, it was a golf club. It 1952, the Brandts bought it and changed it back to a camp, but this time for children. The first season was in 1953. It was a co-ed camp, and it was very beloved and successful. Alas, there was a tragic accident involving several counselors in 1967. The camp never really recovered. It closed in 1970. Bob Katzman and Errol Blank bought it and created the Arcady Bay estates development.

A cottage at Arcady

Many of Hague's earliest settlers were buried in this cemetery during the years 1803-1870. Watch a video posted by a visitor to the cemetery.

Travel by steamboat was the only option for getting to locations on the lake in the 1800s.

The Lake George Steamboat Company was founded in 1817 and still operates today. In the 1800s, every town and most major hotels had steamer docks. If there were so passengers, the crew of the steamboats would throw the mail into the hands of a town/hotel employee waiting on the dock.

The first steamboat to ply the waters of Lake George was the James Caldwell (1817-1821). During the William Caldwell’s lifespan, the Lake George Steamboat Company used it to ferry travelers from Lake George Village to Ticonderoga. Starting at 8 a.m., the steamboat would leave the Lake House in the village, travel north to Ticonderoga for 3.5 hours, let passengers explore the area and Fort Ticonderoga’s old ruins, and then return home by 6:30 p.m. The next boat was the Mountaineer; it sailed from 1824 to 1836. The John Jay sailed from 1854 to 1856, when it burned off Calamity Point in Hague. The Mini-Ha-Ha was built in 1857 and could hold 400 people, but that wasn’t enough due to the hotels opening up and down the lake. The Ganouskie was built in 1869.

The Delaware and Hudson Railway took over ownership of the Lake George Steamship Company and coordinated the rail and steamboat schedules. The Mini-Ha-Ha was retired and a new ship called the Horicon was built. This new ship offered elegant salons and cabins. In 1884, the Ganouskie was retired and the Ticonderoga was built. Alas, it burned in Heart Bay in 1901. The first of the Mohicans was built in 1884 and ran until 1908, when it was replaced by the Mohican II. The first steel-hulled ship to ply the lake was the Sagamore. It sailed from 1902 to 1927 when it nicked Anthony’s Nose and had to be put ashore in Glenburnie. It was repaired but ultimately retired in 1932 due to the Great Depression. The Horican II (1912-1939) started out making trips up and down the lake but later became a showboat, featuring music and dance cruises to entice new passengers.

In the late 1920s, a highway over Tongue Mountain completed the road connection between Lake George and Ticonderoga; this took traffic away from the steamboat company. The Mohican (II) continued to sail and was the only passenger-carrying vessel on the lake during World War II. Wilbur Dow purchased the company in 1945. He bought a retired navy ship and renamed it the Ticonderoga II; it sailed from 1950 to 1989. He also added modern features to the Mohican (II) and replaced the ship's wooden hull with steel. Thus the Mohican still sails Lake George today, along with the Mini-Ha-Ha II and the Lac Du San Sacrament.

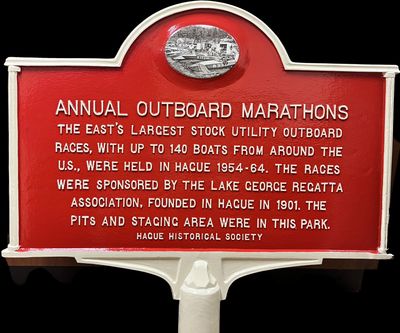

From 1954-1964, a small group of local men and women dreamed big and brought their dream to fruition. With little other than unbridled enthusiasm and an unstoppable can-do attitude, they relaunched the Lake George Regatta Association (LGRA), which was founded in Hague in 1901 but had ceased operating in 1929. They convinced the American Power Boat Association to sanction the Hague races, which earned the town a slot on APBA’s national circuit. For one August weekend every year, stock utility outboard race boats and their drivers took over the town. At its peak, the Northern Lake George outboard marathon attracted nearly 150 racers and their families.

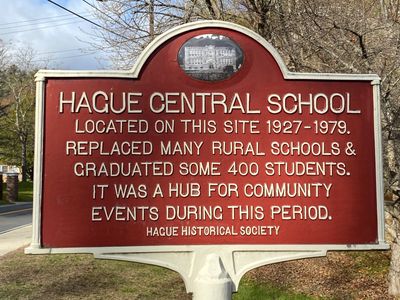

Initially, Hague sported eight district schools in different parts of town. In 1927, nearly a decade before other nearby rural towns, Hague consolidated the districts into a centralized school, which became the heart of the town.

The Hague Central School building served the town from 1927 to 1979 and graduated approximately 400 students over the course of that time. Throughout the school's last decades, the athletic teams competed in the old Marcy League in soccer, basketball and baseball. The mascot, the Raiders, depicted by a Native American, sported red and gray colors at first and in later years, red and white. Between 1977 and 1979, the Hague Raiders’ basketball team advanced to post-season play, culminating in an appearance in the Capital District semifinals in 1979.

In the 1970s, with a dwindling K-12 student population, the decision was made to consolidate Hague with the Ticonderoga school system, and Hague Central School closed in 1979. The building was razed in 1985, and the current Hague Community Center was built on its site.

The Hague Historical Society has a wonderful selection of yearbooks in its collections as well as sports uniforms and trophies.

A Hague farmer named Sam Ackerman, logging in the snow sometime during the 1880s, stripped the cover from a rock outcropping. Tree trunks skidded over that rock came up with dark smudges….evidence of graphite. The word reminds most people of the lead in pencils but that's a minor use. Graphite primarily serves in manufacturing crucible steel, in electrochemistry, as a paint pigment, and as a lubricant. And in industrializing America, it was a necessity.

Now, Adirondack graphite had appeared before, but not in amounts that proved commercially workable. This strike was different. Samples forwarded to the American Graphite Company in Jersey City, New Jersey tested out for high content and the company (which was later absorbed by the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company) quickly went into action. By 1888, a bustling town appeared on the previously unsettled mountainside, workers and their dependents had moved into new frame houses, and the first mill was built. That mill burned down in 1891, but a larger one (500’ x 100' and more than two stories high) replaced it.

As the mine prospered so did the community. An updated blueprint shows a hose house (coal fires plus wooden buildings equal danger, as the fate of the first mill had shown ), a blacksmith shop for shoeing horses and repairing machinery, a coal shed, saw mill, a plant office, the post office (with daily delivered deliveries from Ticonderoga, 15 miles away), a company store, a barn to shelter 20 teams of horses, and at the edge of town a powder magazine. There was also a boarding house that could accommodate 80 to 100 persons.

With the effort to push for a post office, the name of Graphite put the town on the map. The mine superintendent, George Hooper, recommended the name when "Hague Mines" and "Dixon " were rejected. George Hooper, son of William Hopper, supervisor of the American Graphite Company mill in Ticonderoga, ran the works at Hague using machinery designed and patent it for that purpose by his father.

The largest house in Graphite housed the superintendent's family. The other buildings in town were a privately owned store, a boarding house (with more than 50 patrons in 1903), several "tenements"(presumably men's dormitories), company-owned houses for married staff and some private homes, perhaps 25 altogether. Most are labeled with the occupants names, but outside the village center the blueprint list the "Italian "store, a house designated only as "Italian" and "Italian" shanty and an "Italian" Pine house, evidence that the great Italian immigration wave of the 1890s had reached even distant Warren County . Russians were later brought from New York to work the mines. In addition, there was a livery stable, a two-room school house for two teachers and 60 pupils, the Echo Mountain Social Hall, a poolroom, and three bars. There was a movie house on the main road.

Men working the shovels and dynamite opened the hillsides and created miles of tunnels. In their heyday, the mine digging required 80 men, with another 20 supporting them above ground. Fifty more worked in the mill, which ran double shifts in peak periods Beginner’s pay was 10 cents an hour; the average pay rate was $1.25 for a 10-hour workday. About 250 men were employed at the minds during World War I.

"In 1890," local historian Clifton West records, "Hague had 682 persons listed in the census. By 1900, with the mining operation, the township had 1042 residents. This level was maintained through 1920. During the next decade the mill closed, and by 1930 our population had fallen to 741."

After the mines closed, a watchman was kept there for about two years. The machinery was sold or junked. Some of graphite buildings burned, others were abandoned, and some were moved away. The mill was torn down and its boilers were carried off to Silver Bay to provide heat for a hotel there. Today, trees and weeds grow out of the old foundations at Hague and a marina occupies the place of the graphite dock.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.